Microscopic Monarchs: What the Discovery of Four New Wasp Species in West Bengal Tells Us About Science, Society, and Survival

When scientists at the Zoological Survey of India (ZSI) recently unveiled the discovery of four new species of minute parasitoid wasps in West Bengal, it made a brief ripple in the Indian scientific community—but hardly a wave in public discourse. And yet, hidden beneath this seemingly minor update is a story with planetary resonance. These tiny insects—each less than a millimeter long—offer profound insight into biodiversity, ecological intelligence, overlooked science, and our relationship with nature itself.

The Discovery: Four Ghosts in the Garden

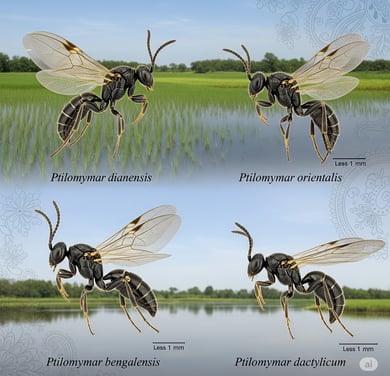

The four newly identified wasps—Ptilomymar dianensis, Ptilomymar orientalis, Ptilomymar bengalensis, and Ptilomymar dactylicum—are part of the fairyfly family (Mymaridae), a group of parasitoid wasps so small they can float on water tension and are sometimes mistaken for dust motes. Found in agricultural zones, wetlands, and forest fringes of West Bengal, these species are crucial bioindicators and natural pest managers.

What’s remarkable is not just their biology, but the fact that they’ve remained undiscovered despite being present in relatively accessible ecosystems. Their unveiling is not just a feat of taxonomy—it’s a mirror held up to our scientific blind spots.

1. Discovery or Delay? A Taxonomic Time Bomb

The real question isn’t why these wasps are new. It’s why they were only discovered now.

India is home to over 90,000 documented animal species, yet estimates suggest this could represent just 50% of the actual number. Taxonomic science—the backbone of biodiversity documentation—is underfunded, often overlooked, and viewed as "non-urgent" within larger scientific agendas. There’s a dangerous irony here: the longer we delay identifying species, the more likely they are to disappear before we even know they existed.

The discovery of these wasps isn’t just a moment of triumph. It’s a warning. How many species have gone extinct silently because no one was looking in time?

2. Tiny Wasps, Titan Impacts: Ecological Engineers in Disguise

Fairyflies are parasitoids—biological control agents that lay their eggs inside the eggs of pests such as aphids, thrips, and leafhoppers. Upon hatching, the larva consumes the host from within. In the agricultural theater, these wasps are unsung heroes, reducing the need for pesticides, thereby protecting both human health and soil ecology.

India is the world’s largest producer of several crops but also one of the highest pesticide consumers, often with devastating health and environmental consequences. These wasps, if studied further, could offer a route to low-cost, sustainable agriculture, particularly for smallholder farmers who suffer most from pesticide overuse and rising input costs.

3. The Bengal Lens: Why This Location Matters

That these discoveries were made in West Bengal is symbolically potent. Bengal, once a hub of natural history during British colonial times, has seen a steep decline in field biology resources. Yet its riverine ecosystems, mangrove borders, and humid agro-climatic zones make it a hotspot for overlooked biodiversity.

The wasps weren’t found deep in the Amazon or a remote Himalayan valley—they were in rice paddies and semi-urban fringes, suggesting that biodiversity is thriving (and hiding) even in human-altered landscapes. This challenges a common conservation myth: that pristine wilderness is the only space worth saving.

4. Insects in the Anthropocene: The "Sixth Extinction" from the Ground Up

Global entomologists have been sounding alarms over insect population collapses—a phenomenon dubbed “Insectageddon.” With pollinators, decomposers, and pest controllers vanishing, ecosystems are losing their scaffolding.

These newly discovered wasps offer a counterpoint. Not all is lost. Nature, it seems, still holds secrets—some of which may help reverse the damage we’ve done. But time is short. The same processes that obscure our knowledge—urban sprawl, monocultures, pollution—also endanger what we haven’t yet found.

5. A Cultural Disconnect: Why Don't We Care About Wasps?

Culturally, we revere tigers and elephants but revile insects. We invest in tiger reserves, not insectariums. But the problem runs deeper. Tiny species are often seen as biologically insignificant and emotionally unrelatable—invisible not just to the eye, but to empathy.

This speaks to a narrative failure. Science must do more than name species—it must tell their stories in ways that connect to policy, agriculture, climate, and culture. A wasp may not have charisma, but it has consequence.

6. The Opportunity: Reimagining Discovery as Development

India spends billions on infrastructure, yet the economic value of ecosystem services from insects remains unaccounted in GDPs. This is short-sighted. If even one of these new wasps proves useful in pest control, its impact could cascade through supply chains, reducing agrochemical imports, improving yields, and restoring biodiversity.

Investing in taxonomic science isn’t just ecological—it’s economic, agricultural, and even geopolitical. Owning our biodiversity means owning our solutions.

Conclusion: The World Through a Wasp’s Wing

This discovery is not just a marvel of biological science—it’s a microcosmic message. It reminds us that knowledge is incomplete, that our understanding of the natural world is shallow, and that neglecting the small is often our greatest mistake.

In a time of climate anxiety, zoonotic spillovers, and ecological collapse, the ZSI’s discovery is a rare flicker of hope. Not because four new wasps will save the world—but because they show us that the world still has more to give, if only we bother to look.